A Year of Contradictions

The end of Fortress Australia?, a first birthday for Man of Contradictions, why writing is thinking, and the other love of my life

Happy September subscribers - yes it is September, and yes the months do seem to pass by like ships in the night when you’re in lockdown.

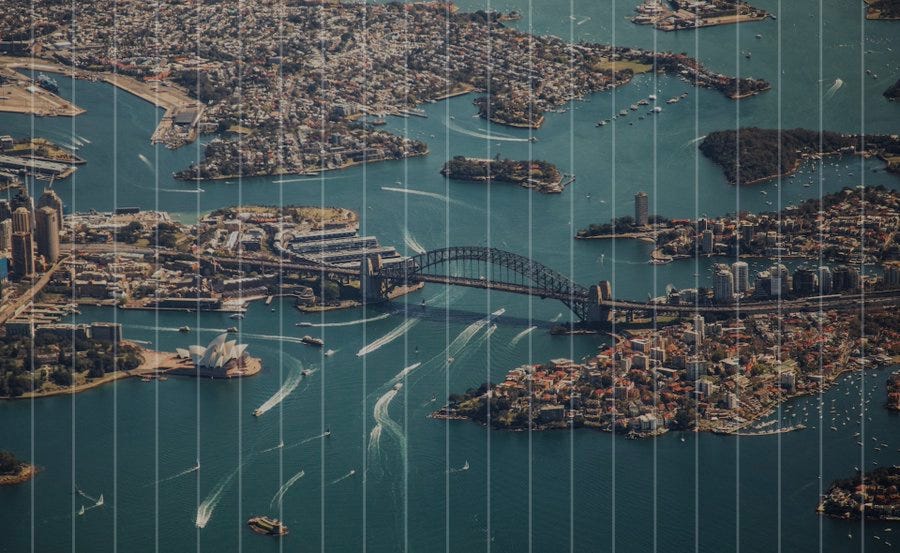

Here in Sydney, we’re all hoping for better news as the vaccination rate ticks up and initial plans for opening up have been unveiled.

People sometimes mistake me for a pessimist because I like to think about worst-case scenarios as well as the best cases. But I find that being forewarned and forearmed is a much better - and happier - way to navigate difficult situations and problems.

Which brings me to…

The end of Fortress Australia?

Colleagues at the Lowy Institute have just published a series of short essays that highlight the costs of Australia’s extremely tight border policies, and call for a better way forward that embraces more openness and more targeted restrictions.

In my own piece, I argued that Australia’s relationships with Southeast Asia have suffered across a number of fronts:

High-level diplomacy: as I’ve written before, Zoom just doesn’t cut it in Southeast Asia and Australian ministers have been very reluctant to hit the skies. Rivals such as China and allies such as the UK have been far more active in the region. Hopefully this is changing, with the the Australian foreign and defence ministers travelling to Indonesia, India and South Korea, before the AUSMIN meetings in Washington. If you want to be counted, you have to show up, as China’s Wang Yi knows, having met Indonesian counterpart Retno Marsudi four times in person since the pandemic began, compared to one meeting for Marise Payne and Retno.

Business: China’s widespread embargo on trade with Australia has heightened the need for diversification. That is easier said than done at the best of times. The various Australian government initiatives to promote more trade and investment with Indonesia, India and Vietnam are unlikely to make much headway until investors and exporters can start travelling again. It would be a brave entrepreneur to start a business in these markets without being on the ground first.

People-to-people: People matter too, as well as businesses and diplomats. Many Australians and Australian residents with family in Southeast Asia and vice versa (full disclosure: that includes me) have been separated from loved ones for a long time now. Tens of thousands of Southeast Asian students have not been able to take up places at Australians universities despite paying high tuition and visa fees. Australian students who would be undertaking potentially life-changing internships and exchanges are stuck with Zoom sessions.

With more jabs going into arms across the country, home quarantine on the cards and all states and territories agreeing, in theory, to a reopening plan, there is cause for hope. But, while not directly comparable, Singapore’s experience shows that going from a tightly controlled no/low COVID-19 policy to a more open one is likely to be a bumpy path.

Beyond the technical questions about how to open up safely, there is a bigger, as yet unanswered question, about whether the pandemic has reawakened in Australians a desire for a smaller, more inward-looking country or if this is a passing trend brought about by extraordinary circumstances. Answers on a post card please.

First birthday for Man of Contradictions

It doesn’t feel like it in these days when time seems to simultaneously stand still and speed up, but it’s been a year since I published my second book: Man of Contradictions: Joko Widodo and the Struggle to Remake Indonesia.

It’s been a wild ride.

In that time, my book has been reviewed/cited/extracted/praised by, to name a few, The Economist, the Financial Times, Foreign Affairs, the Sydney Morning Herald, the Australian Financial Review, Nikkei Asia, the Times Literary Supplement, the Literary Review, Reuters, Tempo, the Jakarta Post, Kompas, the New Left Review, the Straits Times, the New Straits Times, the Business Times, South East Asia Research and Contemporary Southeast Asia.

I’ve given virtual book talks to, among others, CSIS Indonesia, CSIS in Washington, the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore, the Ubud Readers and Writers Festival, the Australian National University, the Perth US-Asia Centre, the Royal Society for Asian Affairs, and Thailand’s Institute of Security and International Studies. I’ve given private briefings to many business groups, government departments and foreign ministries around the world.

And Man of Contradictions has been republished in a new edition for the Southeast Asian market, the first Lowy Institute/Penguin Random House book to be picked up by an international publisher.

My book has also been slammed by a leading Indonesianist. It’s been dismissed by a former Jokowi adviser based on some free word cloud software. And it’s been weaponised by diehard supporters and opponents of Jokowi as a sign of how great/terrible a leader he is. Some of these netizens have even been enthusiastic enough to send me abuse/threats on a regular basis. So, taking it all together, I must be doing something right.

The biggest compliment, however, comes from Indonesia’s entrepreneurial book piracy industry, which has produced a dizzying array of ersatz editions, as seen in this screengrab from a leading ecommerce site. (If you prefer the real thing, ask at your local book store, check out your local Amazon site, or buy it with free global delivery from Book Depository.)

Now for book three…

Writing is thinking

Over nearly twenty years as an analyst, author and journalist, one of the best lessons I’ve learned is that writing is thinking. Writing an article, analysis paper or a book is not just about producing a specific output with a specific argument/focus. It’s a process to help you work out what you really think/believe about an issue; to guide your future thinking; and to prompt discussion/debate with others that will further enrich your thinking.

This newsletter has also been a great tool to help sharpen my thinking so thanks for reading/subscribing/sending feedback.

A couple of the issues I grappled with recently here have made their way into fully-formed op-eds/analyses.

For Nikkei Asia, I argued that we shouldn’t be surprised about ASEAN’s failure to make any headway on tackling the Myanmar crisis:

It took ASEAN four months to appoint an uninspiring Bruneian diplomat as its special envoy to Myanmar. But it has still not put any significant pressure on Myanmar's military regime and has avoided high-level talks with the country's ousted democratic leaders. The organization's response is certainly lamentable. It is not, however, surprising.

Some Southeast Asian critics have accused Brunei -- the tiny, wealthy sultanate that holds the rotating annual ASEAN chair -- of mishandling its leadership role since the February military takeover.

But Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah, who serves concurrently as prime minister, defense minister, finance minister and minister of foreign affairs, is no diplomatic naif. He has been attending meetings of ASEAN leaders since 1987, when his counterparts included Suharto, Lee Kuan Yew and Mahathir Mohamad.

Rather than reflecting Brunei's deficiencies, ASEAN's stance on Myanmar reflects the fundamental character of the organization, and the region. While it is right to hope for more from ASEAN, it is important to understand its limitations rather than wish them away.

For The Interpreter, I pondered the UK’s Indo-Pacific Tilt and the challenge the UK faces to maintain the pace and depth of engagement with Southeast Asia and ASEAN - a point made for me this week when PM Boris Johnson sacked Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab, who had spearheaded renewed engagement with SE Asia, over his mishandling of the Afghanistan withdrawal.

The United Kingdom will need to work harder bilaterally in Southeast Asia, as well as through the many ASEAN mechanisms. It should also use its ASEAN platform to intensify collaboration with other like-minded external partners in Southeast Asia, including Australia, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea and the United States.

Britain’s renewed focus on Southeast Asia has broadly been welcomed in the region, from a first trip by a foreign secretary to Cambodia in 68 years, to the first-ever visit by a defence secretary to Vietnam. But, from Washington to Canberra, Western officials have a history of rediscovering Southeast Asia only to lose interest when the going gets tough.

The other love of my life: Brentford FC

Last, but by no means least, I want to draw your attention to the other great love of my life (apart from Southeast Asian politics): Brentford Football Club. Newly promoted to the Premier League, we beat Arsenal 2-0 on the first day of the season, which lifted my lockdown blues. I don’t think I’ve ever had a better 5am start than this:

I wrote an essay about my 27-year journey with Brentford from the depths of lower-league despair to Premier League glory, reflecting on what football, family, identity and home mean to me. Here’s a flavour:

While top football teams have become globalised brands, you couldn’t say that of Brentford. At least it is not the sort of brand that many sane people would pay to associate with. Brentford is more of an immersive sentient experience.

For you don’t just watch Brentford. You smell it. The wafts of beer and cigarette smoke as you pass the pubs. The aroma of ageing metal and oil as you squeeze through the tiny turnstiles at Griffin Park. The heady scent of steaming pies and burgers filled with indeterminate meat.

And you hear Brentford. The jokes, the insults, the songs. The roar of a goal celebration reverberating off the tinny Griffin Park stands. The rapid-fire applause after a desperate, lunging save by the goalkeeper. And the horror, on my part, at the occasional (but not rare enough) racist abuse or chant.

It’s not pretty. But it’s Brentford. Life at its best and worst.

I’ve lived most of my adult life overseas, working as a journalist and foreign policy analyst in Singapore, Indonesia, Vietnam, China and now Australia. Brentford has always made this citizen of nowhere feel like he has a somewhere too.

As Pascal Mercier writes in Night Train to Lisbon: “We leave something of ourselves behind when we leave a place; we stay there, even though we go away. And there are things in us that we can find again only by going back there.”

That’s why, every year before the pandemic, I would travel thousands of miles back home to find that part of me that only exists in that little stadium in West London

You can read the rest here.

Thanks for subscribing and, if you’ve found Bundle of Contradictions useful, interesting or pleasantly distracting, do subscribe and/or share it with others.

Take care out there.

Ben