Language, diplomacy and law (in lockdown)

The UK's Indo-Pacific Tilt, mutual (mis)understanding between Australia and Indonesia, and what Franz Kafka tells us about Hong Kong's legal system

Greetings long-suffering readers and new subscribers. Thanks for the interest in my scribblings.

I’m still in lockdown in Sydney so have few exciting personal developments to report. But, after going through the first five stages of lockdown grief (Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression and Doom-scrolling), I’m hoping that I’ve finally arrived at Acceptance.

I got there thanks to endless socially distanced walks around my neighbourhood, and the Olympics. Thank you Tokyo for persevering. I’m not sure what I would have done without you. Never before have I been so excited to watch Badminton (well done Indonesia!), Diving and the Balance Beam.

Weighing the UK’s Indo-Pacific “Tilt”

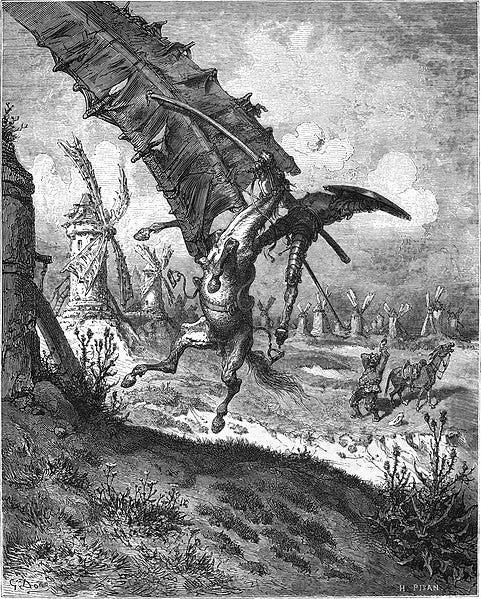

The US took the “Pivot” and the “Rebalance”. Australia did a “Step-up” in the Pacific, accompanied by an unannounced step-down in Southeast Asia. Indonesia preferred a Pacific “Elevation”. That left the UK with few rhetorical options when it unveiled its own ambitions to increase its focus on the Indo-Pacific. So “Tilt” it is, a rather unfortunate linguistic choice that immediately brought to mind Don Quixote and windmills.

While many political scientists and foreign policy analysts are obsessed with nomenclature, my first principle is: ignore the rhetoric, look at the reality. New buzzwords are usually more spin than substance.

In my new, additional guise as a non-resident Senior Research Fellow at the Foreign Policy Centre, a UK think-tank, I took a stab (not a tilt) at examining the new UK approach, which is part of the Integrated Review of foreign and defence policy released in March.

I’ve been impressed by the energy with which the British government has engaged Southeast Asia over the last year, at a time when travel has been very difficult. It matters, I believe, who shows up in troubled times. Dominic Raab, the foreign secretary, has been to SE Asia twice in the last few months and has hosted SE Asian ministers in London on several occasions. He made the first visit by a British foreign secretary to Cambodia since 1953, while Ben Wallace recently completed the first ever official visit to Vietnam by a British defence secretary.

The upshot of this diplomacy, and earlier work, is that ASEAN has agreed to make the UK its first new Dialogue Partner in years and that the UK’s bid to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership is making some initial headway.

But, and you knew there was a but coming, the UK is re-discovering that threading the needle between values and interests in SE Asia will be very difficult. While Raab has taken a very principled stance on the coup in Myanmar, all the talk of democracy evaporated when he set off to make nice with the Vietnamese Communist Party and Cambodian dictator Hun Sen.

This is the essential conundrum for the UK, as well as the US, Australia and other Western allies, as they intensify their focus on SE Asia, with China on their minds:

The increasing talk in London, Washington DC and Canberra of the world dividing into democratic and authoritarian camps will not resonate in Southeast Asia, even in the democracies like Indonesia and the Philippines, which fear Western interference in their systems as much as Chinese.

But the British Government, alongside its US and Australian allies, clearly believes that it cannot rally public support for a potentially costly pushback against China unless it plays the values card.

In Australian foreign policy circles, there’s a tendency (privately) to laugh off Britain’s attempts to re-engage SE Asia as some sort of post-colonial hangover delusion. The uncomfortable truth is that British ministers have enjoyed far more face time of late with their SE Asian counterparts than their travel-shy Australian peers (who’ve been mostly relying on FaceTime instead… or Zoom, or Webex). As the US also steps up its diplomatic engagement in Southeast Asia, Australia needs to elevate its ground game in its own backyard or risk being left behind.

Australia and Indonesia: close but no cigar (or kretek?)

Talking of being left behind, the latest Lowy Institute poll of Australian attitudes to the world contained the usual mix of dispiriting data points about public sentiment toward Indonesia.

On his state visit to Canberra in February last year, which seems a lifetime ago, Indonesian President Joko Widodo called Australia Indonesia’s “closest friend”. His comment was very well received here, although the Indonesian expression he used (“sahabat paling dekat”) is deliciously ambiguous. It can be understood as “nearest friend”, in geographical terms, as well as “best friend”.

In any case, the Lowy poll shows that most Australians don’t feel the same. Only around a quarter of Australians (26%) have some or a lot of confidence in Jokowi to do the right thing in world affairs. That puts Jokowi well ahead of Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping and Kim Jong-un but well behind Narendra Modi, Yoshihide Suga and Angela Merkel.

It’s not just Jokowi. The Lowy data show that Australians have little trust in Indonesia to act responsibly in the world, and Indonesia fares poorly on our feelings thermometer.

As I argued for The Interpreter, the lack of warmth toward and trust in Indonesia is unlikely to change until, at the very least, we’re out of this pandemic and normal travel and people-to-people links can restart.

The good news from the poll is that most Australians are in favour of their government helping SE Asian and Pacific island nations pay for COVID-19 vaccines.

When the previous president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono addressed the Australian parliament in 2010, he outlined four major challenges facing the bilateral relationship: improving mutual public understanding, managing diplomatic differences, boosting economic ties and adapting to emerging regional problems.

Over a decade on, both countries have come a long way on the last three. The Lowy poll reminds us that there is much to do on the first challenge. With a new Australian ambassador in Jakarta, Penny Williams, and a new Indonesian ambassador heading to Canberra soon - Kemlu’s chief thinker Siswo Pramono - now is a good time to come up with ideas for how to improve links across the Timor Sea.

Kafkaesque Hong Kong

Finally, I want to share something I’ve written about Hong Kong. It is a translation into poetic form of a parable called Before the Law, which is contained inside Franz Kafka’s The Trial. I’ve spoken before about the relevance of Kafka’s book to Hong Kong:

The concept of law is more central to life in Hong Kong than any other place I’ve worked in the world. In most democracies, the law tends to play out in the background, barely noticed or commented upon but somehow comforting, like muzak in a lift. In Hong Kong it’s in your face, from the Basic Law to the quasi-religious faith in independent judges and the rule of law. There is no better book than Franz Kafka’s The Trial to smash our illusions about the law into a thousand desolate pieces. For that reason, I probably shouldn’t recommend it. It’s a bit like advising someone to read Albert Camus’ The Plague right now. It’s not exactly solace-inducing. But it’s powerful and apt for Hong Kong today.

In recent years, we’ve seen the law - and the city’s mini-constitution or Basic Law -turned from the seeming foundation of Hong Kong’s freedom and vibrancy to a tool for repression, in increasingly absurd fashion. Kafkaesque, you might say.

Before the Basic Law

Before the Basic Law a gatekeeper stands,

As a man from Hong Kong approaches and demands:

“I want access to the Basic Law!”

“Later,” he replies. “But when, I’m not sure.”

Despite the gatekeeper’s unfortunate denial,

The man peers past him for a little while.

And hoping for the freedom that lies ahead,

He ponders the best path to tread.

Then the gatekeeper just starts to smile,

At the naiveté, almost like a child.

“If you’re so tempted, go forth, don’t plea,”

“After all, you have a high degree of autonomy.”

But, the gatekeeper smugly quips,

“Do not expect the easiest of trips.”

“For I am merely the lowliest of guards,”

“And I too fear the others in many regards.”

At this the man’s crest does start to fall

For shouldn’t the Basic Law be accessible to all?

If even the gatekeeper is too afraid,

Then justice itself must surely be delayed.

Though the way ahead for now is blocked,

There is no need for the man to be mocked.

So the gatekeeper offers him a seat,

And bids him wait for the Basic Law to meet.

While the man does often implore,

The dutiful gatekeeper won’t budge from his door.

Sometimes he asks the man questions though,

About the Hong Kong that he did once know.

But although the man does talk with passion,

The gatekeeper only listens after a fashion.

For while he wishes him not to despair,

About his desires, he does not really care.

Thinking of the promise at the SAR’s advent,

The man begs the gatekeeper finally to relent.

But, the lofty guard simply retorts,

“All I can do is pass on reports”.

Even as his trials make his head feel sore,

The man still expects one day to reach the Basic Law.

So he stays and hopes for the best,

Using all his energy and getting little rest.

As he thus grows old and frustrated,

Over the years and decades he’s wasted,

He gets more desperate and begins to emote,

Pleading even with the fleas in the guard’s wretched coat.

Fifty years now have passed,

And the man will soon breathe his last.

As his body crumbles and his sight fades,

He launches one of his final tirades.

“If I could never reach the Basic Law,”

“Why didn’t you just tell me before?”

The guard, grown weary, fires right back

“Why are you so committed to this miserable track?”

Looking confused, the man then asks,

As he regrets this most futile of tasks,

“If the Basic Law is really meant for all,”

“How come no other passes this wall?”

At this the gatekeeper bursts into laughter,

While the man slips into the hereafter.

“This gate was only ever built for you,”

“But now, of course, it must be closed too.”

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this, feel free to recommend Bundle of Contradictions to a friend, family member or colleague who might be interested. And, if you want your bones further chilled, listen to the version of Before the Law told in Orson Welles’ 1962 adaptation of The Trial.