We need to talk about China-India relations

Asia's most consequential bilateral relationship is rarely analysed with the complexity and depth that it requires

There are many downsides when you transition to “flying a desk” but one of the upsides is being able to commission, develop and nurture talent in your team. I’m particularly proud of my team’s latest paper, which looks at “How China–India relations will shape Asia and the global order”.

China and India have Asia’s most consequential bilateral relationship but it is often looked at through very limited lenses: either from New Delhi’s perspective, Beijing’s perspective or that of the good old West.

My colleagues, Chietigj Bajpaee and Yu Jie, have tried to look at China-India ties in the round, thinking about how Asia’s two great rising powers will shape the future of the region and global governance.

I’d urge you to read the paper in full but here are a few points that I take away:

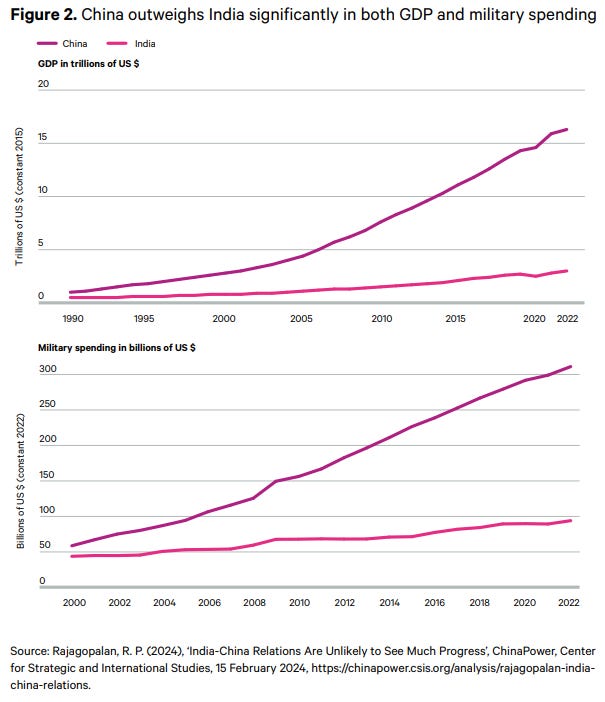

China and India’s geopolitical rivalry goes far beyond their well-covered border disputes, and is based on deep mutual mistrust, competing views of sovereignty and status, and the wide power asymmetry between them.

Both countries like to think of themselves as civilisational states. Yet while India is obsessed with/paranoid about China’s intentions, China tends to view India as a pawn of the West and a major irritant rather than a major rival. Public and elite views in both countries reflect similar mutual misperceptions.

Many of India’s top diplomats view a China posting as key to career advancement but few Chinese diplomats do. Five of India’s last nine foreign secretaries have previously served as ambassador to China. Who was the last top Chinese diplomat to serve in a senior post in India?

But there are also surprising areas of convergence, as both seek to challenge the US/Western-led global order and institutions. These include: adherence to the principle of non-intervention, common positions on freedom of navigation, and the right to communal economic development taking precedence over climate concerns (and individual human rights).

In the midst of a multiyear love affair with India and its Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the US and its allies have lost perspective on India’s worldview and outlook. Desperate for counter-weights to Beijing, they are misreading the drivers of India’s China policy.

While India is unlikely to align against China, it has the potential to become more of alternative pole of economic and geopolitical influence. But if Western partners want to help India move in that direction, they will need to be more realistic in their ambitions and more focused on working with India to reduce its reliance on Chinese technology.

If you want to hear more about this and ask your own questions, the authors and I will be discussing the paper with Nirupama Rao, former Indian foreign secretary and ambassador to China, on May 8 at 8am Washing/1pm London/5.30pm New Delhi/9pm Tokyo. Sign up here to join us in person at Chatham House or online.